I went partying with Lou Rosenfeld, from Rosenfeld Media.

Well... not really, I just ran into him on my way to an ILA19 party in Medellín, and then each went his own way (sorry, I had to start with a powerful sentence).

The relevant thing is that two days later, in the great final talk of the event, Lou Rosenfeld presented the concept of "the prison of moments". I will give you a mega-summary: we become "prisoners" of a moment when we become attached to a concept that is no longer valid. Freeing ourselves from these prisons implies rethinking these concepts and understanding them in a more current context.

Lou gave the example of an Information Architect: the industry has changed so much that, what was once a prominent title, today almost no one has it as a job description on Linkedin.

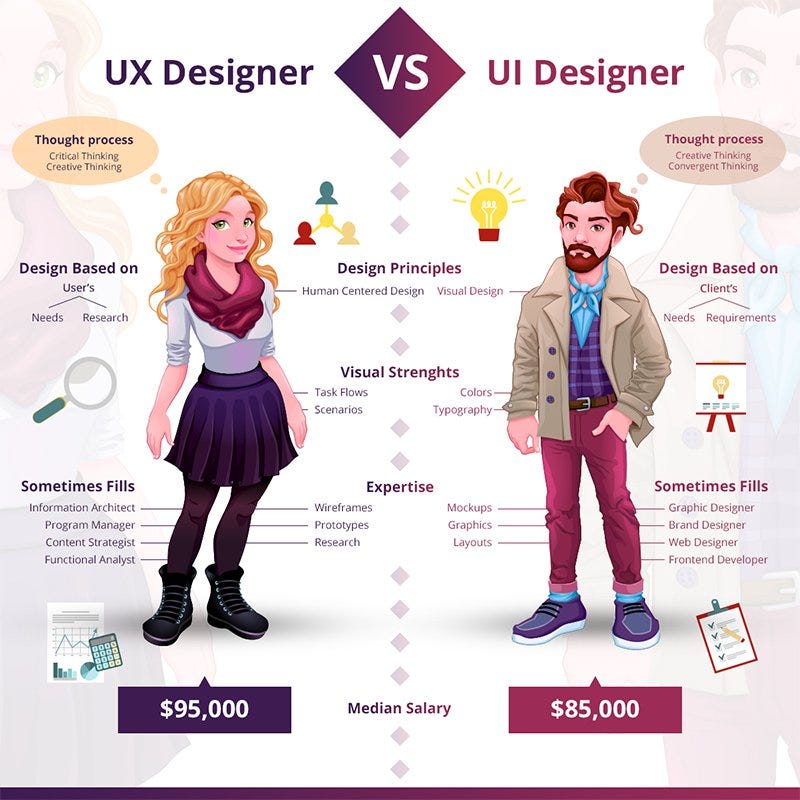

On the flight back I was thinking about this concept and told Paul – UI Designer at Ripley Bank– about it. After listing all of our job responsibilities, Paul capitalized on the discussion with a question: Why does a UX earn more than a UI?

It's funny: in my mind, automatically, a lot of possible answers were generated, but they all started from an old concept of UI, a "prison of the moment".

I took this question to other spaces and got similar answers. The common conclusion (which I also, unconsciously, shared) is that a UI fulfills a "lesser" role than the UX. Under this view, the UX role is more strategic, while the UI role is basically to put color on the screens and maybe suggest a new font, but that's about it.

Where does this idea come from?

What do you think of when I say "UI Designer"?

I recently attended a design community meetup. One of the attendees, a recent Graphic Design graduate, asked how to make the transition to UX. The answer, shared by several other attendees, was: the leap to UX is a big one, first, you have to go through UI.

This idea of the "ladder of progress" is quite recurrent in the design world. Under this concept, UI is a previous version, an internship, that allows you to test the world of digital experiences, and then move up to the world of UX.

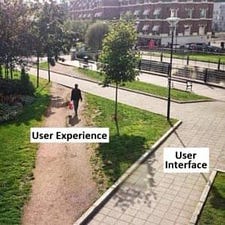

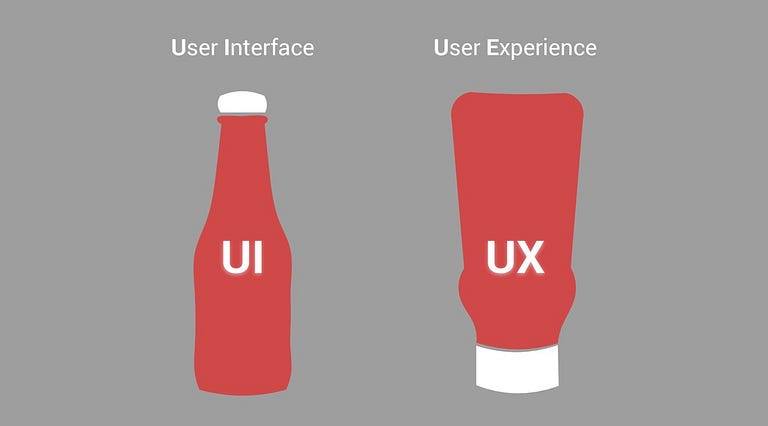

From the same insight that gives rise to this idea, other concepts such as "UX is not UI", or "if it has UI, but no UX, then it is useless" (I have already talked about this myth in another article).

I understand where all this comes from: there was, at the time, a need to reassess the role of UX, giving it that more strategic and holistic twist. To achieve this, a (false?) duality was created between UI and UX. The underlying idea was to move away from the traditional concept ("UX makes cool screens") to one more in line with their work ("UX improves the experience").

Then, the memes came.

This, however, left an empty space: if UX Designers don't beautify interfaces, then who does?

And since the path had already been set, the industry assigned that role to the UI. But in practice, UIs do much more.

The new roles of UX and UI

When the term UX started to become popular, those who grabbed it were basically digital designers hungry for more. So once invited to the buffet, they put everything they could on their plate: business strategy, research tools, management methods, development frameworks, and of course, interaction knowledge.

I know –and have worked with– UX Designers who know little about interaction models, usability, or accessibility, because their role is to understand users, to detect insights, or to build engagement strategies beyond the screens. I don't blame them, nor do I think they did a bad job. On the contrary, I have been lucky to work only with exceptional UX Designers.

On the other hand, modern UI Designers have more contact with screens and more experience landing, in the language of interaction, the needs that a UX has found.

This is my case and that of several UI's in the industry, like Paul: people specialized in interaction, people building structures thought for scalability, in how to transmit brand identity, in how to improve usability, in how to improve accessibility. All of that giving it the creative twist, which is a universe of standardized designs and short timeframes is, as we know, quite difficult.

The escape route from the "prison of the moment".

"Nico, then it will be enough for me to go to my boss and ask for a raise."

But I feel that this goes beyond individual requests or acts. To change the perception they have of us, we need to make a collective effort, involving the entire UI community. The idea is to repeat what UX did at the time when they specialized in business and strategy. I call this process professionalizing the profession.

In essence, professionalizing means going beyond the visual aspect. We have to take on more responsibilities and specialize in this space that is now practically our domain: interaction. Translating this into actions would be, for example:

- To build wireframes, because they are the main tool to talk about interaction with the team.

- Conduct usability tests, because they give us immediate feedback on how well the interaction is working.

- To become, in general, owners of the interaction and of the screens, doing Visual QA and component QA.

This does not mean that this labor is the sole and exclusive responsibility of the UI. But it does mean that we need to start raising our voices and participate, more forcefully, in these decisions.

Nor does it mean "give us more attention because we are great and we deserve it", but to start generating relevance around our work, giving it a more professional-specialized and less artistic-intuitive weight.

This in turn implies adding to our visual background other valuable aspects for interface design: interaction, usability, accessibility, programming fundamentals, interface analytics, etc. Not to mention other soft skills: interpersonal communication to present what we design, teamwork to make delivery more efficient, synthesis capacity, etc.

If we want to break out of the industry's current prison, and as a consequence, earn the same as a UX, this is our job from now on.

Then, when everyone is distracted, we will conquer the world.